And he said, Take heed that ye be not deceived: for many shall come in my name, saying, I am Christ; and the time draweth near: go ye not therefore after them.(Luk 21:8)

Thirty-Five Secrets the Government and the Media Aren’t Telling You about Measles and the Measles Vaccine

As measles outbreaks continue to surface — and as mainstream media weaponizes them for political gain — it’s increasingly difficult to separate fact from fiction.

Is this “public health emergency” truly something to fear? Are we and our children at risk?

To help answer these and many other pressing questions, Children’s Health Defense is offering a free digital download of “The Measles Book” for a limited time.

“The Measles Book: Thirty-Five Secrets the Government and the Media Aren’t Telling You about Measles and the Measles Vaccine” will help you determine whether this is just another example of media, government, and industry misinformation or whether we really have something to worry about.

“The Measles Book” presents reliable medical information from credible sources. Within the book’s pages, the reader will discover 35 secrets being kept from the general public about childhood vaccines, especially the measles vaccine, including:

Learn the other 31 secrets when you read “The Measles Book” by Children’s Health Defense, a nonprofit organization committed to the health of our children and challenging misinformation spread by Big Pharma, government and media. The information in “The Measles Book” helps parents make informed decisions for their children.

The USAID gave roughly $473 million to the “Internews Network,” a secretive global non-governmental organization that allegedly supported online censorship efforts, according to documents released by WikiLeaks.

This article was originally published by The Defender — Children’s Health Defense’s News & Views Website.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) gave roughly $473 million to a “secretive” nonprofit organization that supported efforts to censor social media users, according to documents released by WikiLeaks.

Continue reading USAID Bankrolled Secretive Nonprofit Global News Network With Alleged Ties to CensorshipAccording to documents obtained by Children’s Health Defense, reports of injuries and deaths following COVID-19 vaccines — including a child injured by the Pfizer vaccine during a clinical trial and a fatal vaccine-induced case of myocarditis — reached NIH researchers, Dr. Anthony Fauci and others in 2021 and 2022.

This article was originally published by The Defender — Children’s Health Defense’s News & Views Website.

Several adverse event reports from people injured by the COVID-19 vaccines reached National Institutes of Health (NIH) researchers in 2021 and 2022 — including a report of a child injured by the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine during a clinical trial, according to documents obtained by Children’s Health Defense (CHD).

Continue reading 300 Pages of Emails Leave No Doubt: Fauci, NIH Knew Early on of Injuries, Deaths After COVID ShotsIt is time to stand up for what you believe in.

***There is some flashing imagery in this video***

Continue reading Pagan-Catholics & Lucifer

INTERNATIONAL DIPLOMACY &PUBLIC POLICY CENTER,LLC

U.N.Peacekeeping: Few Successes, Many Failures, Inherent Flaws

by Thomas W. Jacobson

President, International Diplomacy & Public Policy Center, LLC

Visiting Fellow for, and brief published by, the Center for Sovereignty & Security, a division of Freedom Alliance

March-‐April 2012

The United Nations Charter states that it was founded, in part, to

“to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war.”

Comments By Euronews and Associated Press • last updated: 22/10/2020 – 10:35

Pope Francis – Copyright Gregorio Borgia/AP

Pope Francis became the first pontiff to endorse same-sex civil unions on Wednesday, sparking cheers from gay Catholics and demands for clarification from conservatives given the Vatican’s official teaching on the issue. Continue reading Pope Francis gives landmark endorsement of same-sex civil unions

ENCYCLICAL LETTER

FRATELLI TUTTI

OF THE HOLY FATHER

FRANCIS

ON FRATERNITY AND SOCIAL FRIENDSHIP

1. “FRATELLI TUTTI”.[1] With these words, Saint Francis of Assisi addressed his brothers and sisters and proposed to them a way of life marked by the flavour of the Gospel. Of the counsels Francis offered, I would like to select the one in which he calls for a love that transcends the barriers of geography and distance, and declares blessed all those who love their brother “as much when he is far away from him as when he is with him”.[2] In his simple and direct way, Saint Francis expressed the essence of a fraternal openness that allows us to acknowledge, appreciate and love each person, regardless of physical proximity, regardless of where he or she was born or lives.

Continue reading FRATELLI TUTTI – Brothers All -POPE Francis

The Fourteenth Ordinary General Assembly of the Synod of Bishops will contain “a great part of the episcopate,” with many participating bishops being elected by their peers.[From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia]

The Synod fathers include

| The Pope | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Papacy began | 13 March 2013 |

| Predecessor | Benedict XVI |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 13 December 1969 by Ramón José Castellano |

| Consecration | 27 June 1992 by Antonio Quarracino |

| Created Cardinal | 21 February 2001 by John Paul II |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Jorge Mario Bergoglio |

| Born | 17 December 1936 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Residence | Domus Sanctae Marthae |

| Previous post | Provincial superior of the Society of Jesus in Argentina (1973–1979) Auxiliary Bishop of Buenos Aires (1992–1997) Titular Bishop of Auca (1992–1997) Archbishop of Buenos Aires (1998–2013) Cardinal-Priest of San Roberto Bellarmino (2001–2013) Ordinary of the Ordinariate for the Faithful of the Eastern Rites in Argentina (1998–2013) President of the Argentine Episcopal Conference (2005–2011) |

| Motto | Miserando atque Eligendo[a] |

| Signature | |

| Coat of arms |  |

Ecuador 7/7/15 Pope Francis told a large crowd, “I ask you to pray fervently for this intention,” the Pope continued, “so that Christ can take even what might seem to us impure, scandalous or threatening, and turn it into a miracle. Families today need miracles!”

Jesus’ miracle was simple, turn away from sin, and come follow me. There is nothing impure, scandalous or threatening about that. For Jesus is none of these. Families need love, charity, mutual respect for each other in Jesus.

However, what the Pope fails to mention is, people need to stop sinning, turn away from sin. There is the impurity, scandal and threat of the message – you need to do something in return- the Pope fails to mention the most important aspect of Jesus’ ministry.

Pope Francis explained his vision for evangelization and missionary activity in Ecuador July 7 2015

We evangelize not with grand words or complicated concepts, but with the joy of the gospel, that fills the hearts and lives of all who encounter Jesus. Continue reading Pope Francis & Evangelization

25/6/2014 Pope warns against DIY Christianity

“I believe in God, in Jesus, but the in church- I don’t care. How many times have we heard this? This is wrong. Continue reading Pope Francis & DIY Christianity

by Michael Salla

July 23, 2014

from Examiner Website

Pope Francis is reportedly preparing a major world statement about extra-terrestrial life and its theological implications. Continue reading Pope Francis & Aliens

updated 5/13/2008 3:57:50 PM ET

VATICAN CITY — The Vatican’s chief astronomer says that believing in aliens does not contradict faith in God. Continue reading Jose Gabriel Funes SJ

NEW YORK (RNS) With Christmas just around the corner, Brother Guy Consolmagno gets a lot of questions this time of year about the star of Bethlehem that led the Magi to Jesus in the manger.

Christians will not immediately need to renounce their faith in God “simply on the basis of the reception of [this] new, unexpected information of a religious character from extraterrestrial civilizations.” Continue reading Father Giuseppe Tanzella-Nitti SJ

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization to promote international co-operation. A replacement for the ineffective League of Nations, the organization was established on 24 October 1945 after World War II in order to prevent another such conflict. At its founding, the UN had 51 member states; there are now 193. The headquarters of the United Nations is in Manhattan, New York City, and experiences extraterritoriality. Further main offices are situated in Geneva, Nairobi and Vienna. The organization is financed by assessed and voluntary contributions from its member states. Its objectives include maintaining international peace and security, promoting human rights, fostering social and economic development, protecting the environment, and providing humanitarian aid in cases of famine, natural disaster, and armed conflict.

During the Second World War, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated talks on a successor agency to the League of Nations, and the United Nations Charter was drafted at a conference in April–June 1945; this charter took effect 24 October 1945, and the UN began operation. The UN’s mission to preserve world peace was complicated in its early decades by the Cold War between the US and Soviet Union and their respective allies. The organization participated in major actions in Korea and the Congo, as well as approving the creation of the state of Israel in 1947. The organization’s membership grew significantly following widespread decolonization in the 1960s, and by the 1970s its budget for economic and social development programmes far outstripped its spending on peacekeeping. After the end of the Cold War, the UN took on major military and peacekeeping missions across the world with varying degrees of success.

The UN has six principal organs: the General Assembly (the main deliberative assembly); the Security Council (for deciding certain resolutions for peace and security); the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (for promoting international economic and social co-operation and development); the Secretariat (for providing studies, information, and facilities needed by the UN); the International Court of Justice (the primary judicial organ); and the United Nations Trusteeship Council (inactive since 1994). UN System agencies include the World Bank Group, the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, UNESCO, and UNICEF. The UN’s most prominent officer is the Secretary-General, an office held by South Korean Ban Ki-moon since 2007. Non-governmental organizations may be granted consultative status with ECOSOC and other agencies to participate in the UN’s work.

The organization won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2001, and a number of its officers and agencies have also been awarded the prize. Other evaluations of the UN’s effectiveness have been mixed. Some commentators believe the organization to be an important force for peace and human development, while others have called the organization ineffective, corrupt, or biased.

Source Wikipedia

For me:

the United Nations as an organization is ineffective, inept, corrupt and biased.

Too many atrocities have taken place, for which the UN has not held the appropriate parties to account due to it’s ineffectiveness, corruption & bias viz

Knights HospitallerFraternitas Hospitalaria

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Active | c. 1099–present |

| Allegiance | Papacy |

| Type | Western Christianmilitary order |

| Headquarters | Jerusalem; later Rhodes, Malta, Rome |

| Nickname(s) | The Religion |

| Patron | Our Lady of Philermos,

Saint John the Baptist |

| Colors | Black & White, Red & White |

| Engagements | The Crusades

Siege of Ascalon (1153) Battle of Arsuf (1191) Battle of Lepanto (1571) Barbary Pirates (1607)Other service in European navies. |

| Website | http://www.orderofmalta.int/?lang=en |

| Commanders | |

| Notable

commanders |

Jean Parisot de Valette, Garnier de Nablus |

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Order of the Knights of Saint John, also known as Order of Saint John, Order of Hospitallers, Knights Hospitaller, and the Hospitallers, were among the most famous of the Roman Catholicmilitary orders during the Middle Ages.The Hospitallers probably arose as a group of individuals who were associated with an Amalfitan hospital in the Muristan district of Jerusalem, which was dedicated to St John the Baptist and founded around 1023 by Blessed Gerard Thom to provide care for sick, poor or injured pilgrims coming to the Holy Land (Some scholars, however, consider that the Amalfitan order and Amalfitan hospital were different from Gerard’s order and its hospital.)[1] After the Latin Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 during the First Crusade, the organisation became a religious and military order under its own Papal charter. It was charged with the care and defense of the Holy Land. Following the conquest of the Holy Land by Islamic forces, the Order operated from Rhodes, over which it was sovereign and later from Malta, where it administered a vassal state under the Spanish viceroy of Sicily.The Order was weakened in the Reformation, when rich commanderies of the Order in northern Germany and the Netherlands became Protestant (and largely separated from the Roman Catholic main stem, remain so to this day). The Order was disestablished in England, Denmark and elsewhere in northern Europe. The Roman Catholic order was further damaged by Napoleon‘s capture of Malta in 1798 and became dispersed throughout Europe. It regained strength during the early 19th century as it redirected itself toward humanitarian and religious causes. In 1834, the order, by this time known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), acquired new headquarters in Rome where it has since been based.Five contemporary, state-recognised chivalric orders which claim modern inheritance of the Hospitaller tradition all assert that “The Sovereign Military Order of Malta is the original order.” Four non-Roman Catholic orders stem from the same root:[2]Protestant orders exist in Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden, and a non-denominational British revival is headquartered in the United Kingdom. The Knights Hospitaller was the smallest group ever to colonise parts of the Americas. At one point in the mid-1600s, they acquired four Caribbean islands, which they turned over to the French and Dutch in the 1660s.

In 603 AD, Pope Gregory I commissioned the Ravennate Abbot Probus, who was previously Gregory’s emissary at the Lombard court, to build a hospital in Jerusalem to treat and care for Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land.[3] In 800, Emperor Charlemagne enlarged Probus’ hospital and added a library to it. About 200 years later, in 1005, Caliph Al Hakim destroyed the hospital and three thousand other buildings in Jerusalem. In 1023, merchants from Amalfi and Salerno in Italy were given permission by the Caliph Ali az-Zahir of Egypt to rebuild the hospital in Jerusalem. The hospital, which was built on the site of the monastery of Saint John the Baptist, took in Christian pilgrims travelling to visit the Christian holy sites. It was served by Benedictine monks.

The monastic hospitaller order was founded following the First Crusade by the Blessed Gerard, whose role as founder was confirmed by a Papal bull of Pope Paschal II in 1113.[4] Gerard acquired territory and revenues for his order throughout the Kingdom of Jerusalem and beyond. Under his successor, Raymond du Puy de Provence, the original hospice was expanded to an infirmary[1] near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Initially the group cared for pilgrims in Jerusalem, but the order soon extended to providing pilgrims with an armed escort, which soon grew into a substantial force. Thus the Order of St. John imperceptibly became military without losing its eleemosynary character.[1] The Hospitallers and the Knights Templar became the most formidable military orders in the Holy Land. Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, pledged his protection to the Knights of St. John in a charter of privileges granted in 1185.

The statutes of Roger de Moulins (1187) deal only with the service of the sick; the first mention of military service is in the statutes of the ninth grand master, Afonso of Portugal (about 1200). In the latter a marked distinction is made between secular knights, externs to the order, who served only for a time, and the professed knights, attached to the order by a perpetual vow, and who alone enjoyed the same spiritual privileges as the other religious. The order numbered three distinct classes of membership: the military brothers, the brothers infirmarians, and the brothers chaplains, to whom was entrusted the divine service.[1]

The order came to distinguish itself in battle with the Muslims, its soldiers wearing a black surcoat with a white cross. In 1248 Pope Innocent IV (1243–54) approved a standard military dress for the Hospitallers to be worn in battle. Instead of a closed cape over their armour (which restricted their movements), they should wear a red surcoat with a white cross emblazoned on it.[5]

Many of the more substantial Christian fortifications in the Holy Land were built by the Templars and the Hospitallers. At the height of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Hospitallers held seven great forts and 140 other estates in the area. The two largest of these, their bases of power in the Kingdom and in the Principality of Antioch, were the Krak des Chevaliers and Margat in Syria.[4] The property of the Order was divided into priories, subdivided into bailiwicks, which in turn were divided into commanderies.

As early as the late 12th century the order had begun to achieve recognition in the Kingdom of England and Duchy of Normandy. As a result, buildings such as St John’s Jerusalem and the Knights Gate, Quenington in England were built on land donated to the order by local nobility.[6] An Irish house was established at Kilmainham, near Dublin, and the Irish Prior was usually a key figure in Irish public life.

After the fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1291 (Jerusalem itself had fallen in 1187), the Knights were confined to the County of Tripoli and, when Acre was captured in 1291, the order sought refuge in the Kingdom of Cyprus. Finding themselves becoming enmeshed in Cypriot politics, their Master, Guillaume de Villaret, created a plan of acquiring their own temporal domain, selecting Rhodes to be their new home, part of the Byzantine empire. His successor, Fulkes de Villaret, executed the plan, and on 15 August 1309, after over two years of campaigning, the island of Rhodes surrendered to the knights. They also gained control of a number of neighbouring islands and the Anatolian port of Halicarnassus and the island of Megiste.

Pope Clement V dissolved the Hospitallers’ rival order, the Knights Templar, in 1312 with a series of papal bulls, including the Ad providam bull, which turned over much of their property to the Hospitallers. The holdings were organised into eight “tongues” (one each in Crown of Aragon, Auvergne, Castile, England, France, Germany, Italy and Provence). Each was administered by a Prior or, if there was more than one priory in the tongue, by a Grand Prior. At Rhodes and later Malta, the resident knights of each tongue were headed by a Bailli. The English Grand Prior at the time was Philip De Thame, who acquired the estates allocated to the English tongue from 1330 to 1358. In 1334, the Knights of Rhodes defeated Andronicus and his Turkish auxiliaries. In the 14th century, there were several other battles in which they fought.[7]

On Rhodes the Hospitallers,[8] by then also referred to as the Knights of Rhodes,[9] were forced to become a more militarised force, fighting especially with the Barbary pirates. They withstood two invasions in the 15th century, one by the Sultan of Egypt in 1444 and another by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II in 1480 who, after capturing Constantinople and defeating the Byzantine Empire in 1453, made the Knights a priority target.

In 1494 they created a stronghold on the peninsula of Halicarnassus (presently Bodrum). They used pieces of the partially destroyed Mausoleum, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, to strengthen their rampart, the Petronium.[10]

In 1522, an entirely new sort of force arrived: 400 ships under the command of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent delivered 100,000 men to the island[11] (200,000 in other sources[12]). Against this force the Knights, under Grand Master Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, had about 7,000 men-at-arms and their fortifications. The siege lasted six months, at the end of which the surviving defeated Hospitallers were allowed to withdraw to Sicily. Despite the defeat, both Christians and Muslims seem to have regarded the conduct of Villiers de L’Isle-Adam as extremely valiant, and the Grand Master was proclaimed a Defender of the Faith by Pope Adrian VI.

After seven years of moving from place to place in Europe, the knights gained fixed quarters in 1530 when Charles I of Spain, as King of Sicily, gave them Malta,[13] Gozo and the North African port of Tripoli in perpetual fiefdom in exchange for an annual fee of a single Maltese falcon (the Tribute of the Maltese Falcon), which they were to send on All Souls Day to the King’s representative, the Viceroy of Sicily.[14][15] The Hospitallers continued their actions against the Muslims and especially the Barbary pirates. Although they had only a few ships they quickly drew the ire of the Ottomans, who were unhappy to see the order resettled. In 1565 Suleiman sent an invasion force of about 40,000 men to besiege the 700 knights and 8,000 soldiers and expel them from Malta and gain a new base from which to possibly launch another assault on Europe.[13]

At first the battle went as badly for the Hospitallers as Rhodes had: most of the cities were destroyed and about half the knights killed. On 18 August the position of the besieged was becoming desperate: dwindling daily in numbers, they were becoming too feeble to hold the long line of fortifications. But when his council suggested the abandonment of Birgu and Senglea and withdrawal to Fort St. Angelo, Grand Master Jean Parisot de Valette refused.

The Viceroy of Sicily had not sent help; possibly the Viceroy’s orders from Philip II of Spain were so obscurely worded as to put on his own shoulders the burden of the decision whether to help the Order at the expense of his own defences.[citation needed] A wrong decision could mean defeat and exposing Sicily and Naples to the Ottomans. He had left his own son with La Valette, so he could hardly be indifferent to the fate of the fortress. Whatever may have been the cause of his delay, the Viceroy hesitated until the battle had almost been decided by the unaided efforts of the knights, before being forced to move by the indignation of his own officers.

On 23 August came yet another grand assault, the last serious effort, as it proved, of the besiegers. It was thrown back with the greatest difficulty, even the wounded taking part in the defence. The plight of the Turkish forces, however, was now desperate. With the exception of Fort St. Elmo, the fortifications were still intact.[16] Working night and day the garrison had repaired the breaches, and the capture of Malta seemed more and more impossible. Many of the Ottoman troops in crowded quarters had fallen ill over the terrible summer months. Ammunition and food were beginning to run short, and the Ottoman troops were becoming increasingly dispirited by the failure of their attacks and their losses. The death on 23 June of skilled commander Dragut, a corsair and admiral of the Ottoman fleet, was a serious blow. The Turkish commanders, Piyale Pasha and Mustafa Pasha, were careless. They had a huge fleet which they used with effect on only one occasion. They neglected their communications with the African coast and made no attempt to watch and intercept Sicilian reinforcements.

On 1 September they made their last effort, but the morale of the Ottoman troops had deteriorated seriously and the attack was feeble, to the great encouragement of the besieged, who now began to see hopes of deliverance. The perplexed and indecisive Ottomans heard of the arrival of Sicilian reinforcements in Mellieħa Bay. Unaware that the force was very small, they broke off the siege and left on 8 September. The Great Siege of Malta may have been the last action in which a force of knights won a decisive victory.[17]

When the Ottomans departed, the Hospitallers had but 600 men able to bear arms. The most reliable estimate puts the number of the Ottoman army at its height at some 40,000 men, of whom 15,000 eventually returned to Constantinople. The siege is portrayed vividly in the frescoes of Matteo Perez d’Aleccio in the Hall of St. Michael and St. George, also known as the Throne Room, in the Grandmaster’s Palace in Valletta; four of the original modellos, painted in oils by Perez d’Aleccio between 1576 and 1581, can be found in the Cube Room of the Queen’s House at Greenwich, London. After the siege a new city had to be built: the present capital city of Malta, named Valletta in memory of the Grand Master who had withstood the siege.

In 1607, the Grand Master of the Hospitallers was granted the status of Reichsfürst (Prince of the Holy Roman Empire, even though the Order’s territory was always south of the Holy Roman Empire). In 1630, he was awarded ecclesiastic equality with cardinals, and the unique hybrid style His Most Eminent Highness, reflecting both qualities qualifying him as a true Prince of the Church.

Following the knights’ relocation on Malta, they had found themselves devoid of their initial reason for existence: assisting and joining the crusades in the Holy Land was now impossible, for reasons of military and financial strength along with geographical position. With dwindling revenues from European sponsors no longer willing to support a costly and meaningless organization, the knights turned to policing the Mediterranean from the increased threat of piracy, most notably from the threat of the Ottoman-endorsed Barbary Corsairs operating from the North African coastline. Boosted towards the end of the 16th century by an air of invincibility following the successful defence of their island in 1565 and compounded by the Christian victory over the Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, the knights set about protecting Christian merchant shipping to and from the Levant and freeing the captured Christian slaves who formed the basis of the Barbary corsairs’ piratical trading and navies. This became known as the ‘corso’.[18]

Yet the Order soon struggled on a now reduced income. By policing the Mediterranean they augmented the assumed responsibility of the traditional protectors of the Mediterranean, the naval city states of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa. Further compounding their financial woes; over the course of this period the exchange rate of the local currencies against the ‘scudo’ that were established in the late 16th century gradually became outdated, meaning the knights were gradually receiving less at merchant factories.[19] Economically hindered by the barren island they now inhabited, many knights went beyond their call of duty by raiding Muslim ships.[20] More and more ships were plundered, from the profits of which many knights lived idly and luxuriously, taking local women to be their wives and enrolling in the navies of France and Spain in search of adventure, experience, and yet more money.[21]

The knights’ changing attitudes were coupled with the effects of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation and the lack of stability from the Roman Catholic Church. All this affected the knights strongly as the 16th and 17th centuries saw a gradual decline in the religious attitudes of many of the Christian peoples of Europe (and, concomitantly, the importance of a religious army), and thus in the Knights’ regular tributes from European nations.[22] That the knights, a chiefly Roman Catholic military order, pursued the readmittance of England as one of its member states — the Order there had been suppressed, along with monasteries, under King Henry VIII — upon the succession of the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I aptly demonstrates the new religious tolerance within the Order.[23] For a time, the Order even possessed a German tongue which was part Protestant or Evangelical and part Roman Catholic.[citation needed]

The perceived moral decline that the knights underwent over the course of this period is best highlighted by the decision of many knights to serve in foreign navies and become “the mercenary sea-dogs of the 14th to 17th centuries”, with the French Navy proving the most popular destination.[24] This decision went against the knights’ cardinal reason for existence, in that by serving a European power directly they faced the very real possibility that they would be fighting against another Roman Catholic force, as in the few Franco-Spanish naval skirmishes that occurred in this period.[25] The biggest paradox is the fact that for many years the French remained on amicable terms with the Ottoman Empire, the Knights’ greatest and bitterest foe and purported sole purpose for existence. Paris signed many trade agreements with the Ottomans and agreed to an informal (and ultimately ineffective) cease-fire between the two states during this period.[26] That the Knights associated themselves with the allies of their sworn enemies shows their moral ambivalence and the new commercial-minded nature of the Mediterranean in the 17th century. Serving in a foreign navy, in particular that of the French, gave the Knights the chance to serve the Church and for many, their King, to increase their chances of promotion in either their adopted navy or in Malta, to receive far better pay, to stave off their boredom with frequent cruises, to embark on the highly preferable short cruises of the French Navy over the long caravans favoured by the Maltese, and if the Knight desired, to indulge in some of the pleasures of a traditional debauched seaport.[27] In return, the French gained and quickly assembled an experienced navy to stave off the threat of the Spanish and their Habsburg masters. The shift in attitudes of the Knights over this period is ably outlined by Paul Lacroix who states:

“Inflated with wealth, laden with privileges which gave them almost sovereign powers … the order at last became so demoralised by luxury and idleness that it forgot the aim for which it was founded, and gave itself up for the love of gain and thirst for pleasure. Its covetousness and pride soon became boundless. The Knights pretended that they were above the reach of crowned heads: they seized and pillaged without concern of the property of both infidels and Christians”.[28]

With the knights’ exploits growing in fame and wealth, the European states became more complacent about the Order, and more unwilling to grant money to an institution that was perceived to be earning a healthy sum on the high seas. Thus a vicious cycle occurred, increasing the raids and reducing the grants received from the nation-states of Christendom to such an extent that the balance of payments on the island had become dependent on conquest.[21] The European powers lost interest in the knights as they focused their intentions largely on one another during the Thirty Years War. In February 1641 a letter was sent from an unknown dignitary in the Maltese capital of Valletta to the knights’ most trustworthy ally and benefactor, Louis XIV of France, stating the Order’s troubles:

“Italy provides us with nothing much; Bohemia and Germany hardly anything, and England and the Netherlands for a long time now nothing at all. We only have something to keep us going, Sire, in your own Kingdom and in Spain.”[29]

It is important to note that the Maltese authorities would neglect to mention the fact that they were making a substantial profit policing the seas and seizing “infidel” ships and cargoes. The authorities on Malta immediately recognised the importance of corsairing to their economy and set about encouraging it, as despite their vows of poverty, the Knights were granted the ability to keep a portion of the ‘spoglio’, which was the prize money and cargo gained from a captured ship, along with the ability to fit out their own galleys with their new wealth.[30]

The great controversy that surrounded the knights’ ‘corso’ was their insistence on their policy of ‘vista’. This enabled the Order to stop and board all shipping suspected of carrying Turkish goods and confiscate the cargo to be re-sold at Valletta, along with the ship’s crew, who were by far the most valuable commodity on the ship. Naturally many nations claimed to be victims of the knights’ over-eagerness to stop and confiscate any goods remotely connected to the Turks.[20] In an effort to regulate the growing problem, the authorities in Malta established a judicial court, the Consiglio del Mer, where captains who felt wronged could plead their case, often successfully. The practice of issuing privateering licenses and thus state endorsement, which had been in existence for a number of years, was tightly regulated as the island’s government attempted to haul in the unscrupulous knights and appease the European powers and limited benefactors. Yet these efforts were not altogether successful, as the Consiglio del Mer received numerous complaints around the year 1700 of Maltese piracy in the region. Ultimately, the rampant over-indulgence in privateering in the Mediterranean was to be the knights’ downfall in this particular period of their existence as they transformed from serving as the military outpost of a united Christendom to becoming another nation-state in a commercially oriented continent soon to be overtaken by the trading nations of the North Sea.[31]

| This section does not cite any references or sources. (February 2011) |

Having gained Malta, the knights stayed for 268 years, transforming what they called “merely a rock of soft sandstone” into a flourishing island with mighty defences and a capital city (Valletta) known as Superbissima, “Most Proud”, amongst the great powers of Europe. However, “the indigenous islanders had not particularly enjoyed the rule of the Knights of St John.” Most Knights were French and excluded the native islanders from important positions. They were especially loathed for the way they took advantage of the native women.[32]

In 1301, the Order was organized in seven Langues, by order of precedence: Provence, Auvergne, France, Aragon, Italy, England, and Germany. In 1462, the Langue of Aragon was divided into Castile-Portugal and Aragon-Navarre. The English Langue went into abeyance after the order’s properties were taken over by Henry VIII in 1540. In 1782, it was revived as the Anglo-Bavarian Langue, containing Bavarian and Polish priories. The structure of langues was replaced in the late 19th century by a system of national associations.

When the Knights first arrived, the natives were apprehensive about their presence and viewed them as arrogant intruders. The Maltese were excluded from serving in the order. The Knights were even generally dismissive of the Maltese nobility. However, the two groups coexisted peacefully, since the Knights boosted the economy, were charitable, and protected against Muslim attacks.[33]

Not surprisingly, hospitals were among the first projects to be undertaken on Malta, where French soon supplanted Italian as the official language (though the native inhabitants continued to speak Maltese among themselves).[34] The knights also constructed fortresses, watch towers, and naturally, churches. Its acquisition of Malta signalled the beginning of the Order’s renewed naval activity.

The building and fortification of Valletta, named for Grand Master la Valette, was begun in 1566, soon becoming the home port of one of the Mediterranean’s most powerful navies. Valletta was designed by Francesco Laparelli, a military engineer, and his work was then taken up by Ġlormu Cassar. The city was completed in 1571. The island’s hospitals were expanded as well. The main Hospital could accommodate 500 patients and was famous as one of the finest in the world. In the vanguard of medicine, the Hospital of Malta included Schools of Anatomy, Surgery and Pharmacy. Valletta itself was renowned as a centre of art and culture. The Church of Saint John the Baptist, completed in 1577, contains works by Caravaggio and others.

In Europe, most of the Order’s hospitals and chapels survived the Reformation, though not in Protestant or Evangelical countries. In Malta, meanwhile, the Public Library was established in 1761. The University was founded seven years later, followed, in 1786, by a School of Mathematics and Nautical Sciences. Despite these developments, some of the Maltese grew to resent the Order, which they viewed as a privileged class. This even included some of the local nobility, who were not admitted to the Order.

In Rhodes, the knights had been housed in auberges (inns) segregated by Langues. This structure was maintained in Birgu (1530–1571) and then Valletta (from 1571). The auberges in Birgu remain, mostly undistinguished 16th-century buildings. Valletta still has the auberges of Castile-León (1574; renovated 1741 by Grand Master de Vilhena, now the Prime Minister’s offices), Italy (renovated 1683 by Grand Master Carafa, now the Malta Tourism Authority), Aragon (1571, now Ministry for EU Affairs), Bavaria (former Palazzo Carnerio, purchased in 1784 for the newly formed Langue, now used as the Government Property Department) and Provence (now National Museum of Archaeology). In the Second World War, the auberge of Auvergne was damaged (and later replaced by Law Courts) and the auberge of France was destroyed.

In 1604, each Langue was given a chapel in the conventual church of St. John and the arms of the Langue appear in the decoration on the walls and ceiling:

Provence: St Michael, Jerusalem

Auvergne: St Sebastian, Azure a dolphin or

France: conversion of St Paul, France

Castile and León: St James the Lesser, Quarterly Castile and Leon

Aragon: St George [the church of the Langue is consecrated to Our Lady of the Pillar Per pale Aragon and Navarre]

Italy: St Catherine, Azure the word ITALIA in bend or

England: Flagellation of Christ, [no arms visible; in Rhodes the Langue used the arms of England, quarterly France and England]

Germany: Epiphany, Austria born by a double-headed eagle displayed sable

Even as it survived on Malta, the Order lost many of its European holdings during the reformation of Western Christendom. The property of the English branch was confiscated in 1540.[35] The German Bailiwick of Brandenburg became Lutheran in 1577, then more broadly Evangelical, but continued to pay its financial contribution to the Order until 1812, when the Protector of the Order in Prussia, King Frederick William III, turned it into an order of merit;[35] in 1852, his son and successor as Protector, King Frederick William IV, restored the Johanniterorden to its continuing place as the chief non-Roman Catholic branch of the Knights Hospitaller.

The Knights of Malta had a strong presence within the Imperial Russian Navy and the pre-revolutionary French Navy. When De Poincy was appointed governor of the French colony on St. Kitts in 1639, he was a prominent Knight of St. John and dressed his retinue with the emblems of the Order. In 1651, the knights bought from the Compagnie des Îles de l’Amérique the islands of Sainte-Christophe, Saint Martin, and Saint Barthélemy.[36] The Order’s presence in the Caribbean was eclipsed with De Poincy’s death in 1660. He had also bought the island of Saint Croix as his personal estate and deeded it to the Knights of St. John. In 1665, the order sold their Caribbean possessions to the French West India Company, ending the Order’s presence in that region.

The decree of the French National Assembly in 1789 abolishing feudalism in France also abolished the Order in France:

V. Tithes of every description, as well as the dues which have been substituted for them, under whatever denomination they are known or collected (even when compounded for), possessed by secular or regular congregations, by holders of benefices, members of corporations (including the Order of Malta and other religious and military orders), as well as those devoted to the maintenance of churches, those impropriated to lay persons and those substituted for the portion congrue, are abolished (…)[37]

The French Revolutionary Government seized the assets and properties of the Order in France in 1792.

Their Mediterranean stronghold of Malta was captured by Napoleon in 1798 during his expedition to Egypt.[16] Napoleon demanded from Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim that his ships be allowed to enter the port and to take on water and supplies. The Grand Master replied that only two foreign ships could be allowed to enter the port at a time. Bonaparte, aware that such a procedure would take a very long time and would leave his forces vulnerable to Admiral Nelson, immediately ordered a cannon fusillade against Malta.[38] The French soldiers disembarked in Malta at seven points on the morning of 11 June and attacked. After several hours of fierce fighting, the Maltese in the west were forced to surrender.[39]

Napoleon opened negotiations with the fortress capital of Valletta. Faced with vastly superior French forces and the loss of western Malta, the Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim negotiated a surrender to the invasion.[40] Hompesch left Malta for Trieste on 18 June.[41] He resigned as Grand Master on 6 July 1799.

The knights were dispersed, though the order continued to exist in a diminished form and negotiated with European governments for a return to power. The Russian Emperor, Paul I, gave the largest number of knights shelter in St. Petersburg, an action which gave rise to the Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitallers and the Order’s recognition among the Russian Imperial Orders.[42] The refugee knights in St Petersburg proceeded to elect Tsar Paul as their Grand Master – a rival to Grand Master von Hompesch until the latter’s abdication left Paul as the sole Grand Master. Grand Master Paul I created, in addition to the Roman Catholic Grand Priory, a “Russian Grand Priory” of no less than 118 Commanderies, dwarfing the rest of the Order and open to all Christians. Paul’s election as Grand Master was, however, never ratified under Roman Catholic canon law, and he was the de facto rather than de jure Grand Master of the Order.

By the early 19th century, the order had been severely weakened by the loss of its priories throughout Europe. Only 10% of the order’s income came from traditional sources in Europe, with the remaining 90% being generated by the Russian Grand Priory until 1810. This was partly reflected in the government of the Order being under Lieutenants, rather than Grand Masters, in the period 1805 to 1879, when Pope Leo XIII restored a Grand Master to the order. This signalled the renewal of the order’s fortunes as a humanitarian and religious organization.

In 1834, the order settled definitively in Rome.[43] Hospital work, the original work of the order, became once again its main concern. The Order’s hospital and welfare activities, undertaken on a considerable scale in World War I, were greatly intensified and expanded in World War II under the Grand Master Fra’ Ludovico Chigi Albani della Rovere (Grand Master 1931–1951).

The Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta, better known as the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), is a Roman Catholic religious order and the world’s oldest surviving order of chivalry.[44] Its sovereign status is recognised by membership in numerous international bodies and observer status at the United Nations and others.[45]

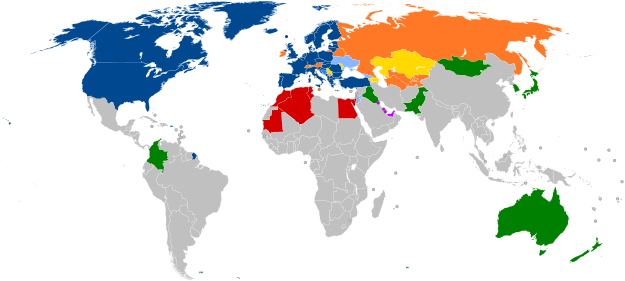

The Order maintains diplomatic relations with 104 countries, with numerous ambassadors. It issues its own passports, currency, stamps and even vehicle registration plates. The Sovereign Military Order of Malta has a permanent presence in 120 countries, with 12 Grand Priories and Sub-Priories and 47 national Associations, as well as numerous hospitals, medical centres, day care centres, first aid corps, and specialist foundations, which operate in 120 countries. Its 13,000 members and 80,000 volunteers and over 20,000 medical personnel – doctors, nurses and paramedics – are dedicated to the care of the poor, the sick, the elderly, the disabled, the homeless, terminal patients, lepers, and all those who suffer. The Order is especially involved in helping victims of armed conflicts and natural disasters by providing medical assistance, caring for refugees, and distributing medicines and basic equipment for survival.

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta recently established a mission in Malta, after signing an agreement with the Maltese Government which granted the Order the exclusive use of Fort St. Angelo for a term of 99 years. Today, after restoration, the Fort hosts historical and cultural activities related to the Order of Malta.[46]

Following the Protestant Reformation, the German commanderies of the Order in the Margraviate of Brandenburg declared their continued adherence to the Order while accepting Protestant theology. As the Johanniterorden (Bailiwick of Brandenburg of the Chivalric Order of Saint John of the Hospital at Jerusalem), the order continues in Germany today, almost autonomous from the Roman Catholic order.

From Germany, this Protestant branch spread into other countries in Europe (Hungary, Poland, the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Switzerland, France, Austria, Great Britain, and Italy among them), the Americas (including the United States, Canada, Mexico, Colombia, and Venezuela), and Africa (most notably in Namibia and South Africa), and to Australia.[47]

The Dutch and Swedish commanderies after World War II became independent orders under the protection of their respective monarchs. In the Johanniter Orde in Nederland, the Dutch monarch is an Honorary Commander; in the Johanniterorden i Sverige, the Swedish monarch is its High Protector.

All three branches (German, Dutch, Swedish) are in formalised co-operation with the Most Venerable Order of Saint John in the Alliance of the Orders of St. John of Jerusalem, just as there is extensive collaboration between these four Alliance Orders and the Order of Malta.

Almost all of the Order‘s property in the kingdom of England was confiscated by Henry VIII during the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Although never formally suppressed, this effectively caused the activities of the English Langue to come to an end; in neighbouring Scotland, however, a few Scottish knights remained in communion with the Order’s French Langue.[48]

In 1831, a British Order was founded by European aristocrats claiming (possibly without authority) to be acting on behalf of the Order.[49] This Order in time became known as the Most Venerable Order of St John of Jerusalem, receiving a Royal Charter from Queen Victoria in 1888, before expanding throughout the United Kingdom, the British Commonwealth and America; the British Order only received recognition from by the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in 1963.[50]

Nowadays, the Order of St John’s best known activities are its running St. John Ambulance Brigade and the St. John Eye Hospital in Jerusalem;[51] the Most Venerable Order has maintained a presence in Malta since the late 19th century.

Following the end of World War II, and taking advantage of the lack of State Orders in the Italian Republic, an Italian called himself a Polish Prince and did a brisk trade in Maltese Crosses as the Grand Prior of the fictitious “Grand Priory of Podolia” until successfully prosecuted for fraud. Another fraud claimed to be the Grand Prior of the Holy Trinity of Villeneuve, but gave up after a police visit, although the organisation resurfaced in Malta in 1975, and then by 1978 in the USA, where it still continues.[52]

The large passage fees collected by the American Association of “SMOM” in the early 1950s may well have tempted a man named Charles Pichel to create his own “Sovereign Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Knights Hospitaller” in 1956.[5] Pichel avoided the problems of being an imitation of “SMOM” by giving his organization a mythical history, claiming that the American organization he led had been founded within the Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitaller in 1908—a spurious claim, but which nevertheless misled many including some academics. In truth, the foundation of his organisation had no connection to the Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitaller. Once created, the attraction of Russian Nobles into membership of Pichel’s ‘Order’ lent some plausibility to his claims.

These organizations have led to scores of other self-styled orders.[5] Another self-styled Order, based in California, gained a substantial following under leadership of the late Robert Formhals, who for some years, and with the support of historical organisations such as The Augustan Society, claimed to be a Polish prince of the Sanguszko family.[5]

In August 2013, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced that the 150,000 square feet (14,000 m2) Hospitaller hospital, built between 1099 and 1291, with permission from the Muslim authorities, had been identified in the Christian Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. It was possible to accommodate up to 2,000 patients, who came from all religious groups, and Jewish patients received kosher food. It also served as an orphanage, with these children often becoming Hospitallers when adult. The remaining vaulted area was discovered during excavations for a restaurant, and the preserved building will be incorporated in the project.[53]

| List of Grand Masters of the Knights Hospitaller

Palace of the Grand Master of the Knights of Rhodes |

Fortifications |

|

|

THE ALLIANCE OF ORDERS

|

![]()

The first master of the original Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem was Brother Gerard (whose origins remain a mystery). Although the original traditions may go further back, we believe that in about 1080, with the help of certain merchants and pilgrims, the Benedictine abbey of St Mary in Jerusalem, in which Gerard was probably a monk, established a hospice close to the Holy Sepulchre compound. Its aim was to tend to pilgrims visiting the city and the holy places nearby, as well as the poor and sick. In 1099, the First Crusade entered Jerusalem – and the fame of Blessed Gerard and his hospital soon spread. The hospital was independently endowed; and the number of brothers (and sisters) grew. Before long, the Brotherhood of Hospitallers, dedicated to St John the Baptist, assumed a military as well as a nursing character. The Knights, as well as tending to our lords the sick and the poor, served as armed guards for the Hospital and escorts for visiting pilgrims, in addition to fighting in support of the Crusader kings and princes.

The Order was formally recognised in 1113. Pope Paschal II issued a Bull in that year establishing it as an independent religious Order with a legal status recognised and approved by the Holy See. Members of the Order (knights, clerics and serving brothers) took vows of chastity, obedience and personal poverty. By the middle of the twelfth century members were wearing on their black robes the eight-pointed cross of St John. The eight points were soon linked to the eight Beatitudes in the Sermon on the Mount; but were later linked to the eight tongues, or divisions of the knights into groups defined by language. The Order flourished and soon spread widely throughout Europe, where it was organised into Bailiwicks, Priories and Grand Priories. Their chief purpose was to channel recruits and funds to the headquarters in the East. Those brothers serving at the headquarters came themselves to be organised along roughly linguistic lines into collegiate bodies called Tongues: Provence, Auvergne, France, Italy, Aragon, Castile, England and Germany. Meanwhile, the Order had shifted its headquarters from the Holy Land to Cyprus; and then to Rhodes and later Malta, which it ruled for two centuries (1530-1798) and from which it took the name, Sovereign Military Order of Malta, by which the Roman Catholic Order is still known today.

On June 13th, 1961, the four Evangelical orders of St. John active in Europe once again came together under the cross of Jesus Christ.

The Johanniter Orders listed below who have signed the Convention correspond to the historic “langues” of the Order. They see themselves as obligated to adhere to the traditional regulations of the Order and the objectives they intend to achieve. However, all of the orders are free, independent and autonomous institutions.

The signatory orders are

as well as the non-German commanderies affiliated with the Balley Brandenburg

The signatory Orders are of the conviction that their mutual history, their faith and their shared objectives demands that they stand unified.

![]()

The Alliance members consist of the four major protestant Orders of St John:

Balley Brandenburg (“Johanniterorden“)

Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem

Johanniterorden I Sverige

Johanniter Orde in Nederland

and four non-German Commanderies of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg:

Swiss Commandery of the Order of St John

French Commandery of the Order of St John

Hungarian Commandery of the Order of St John

Finnish Commandery of the Order of St John

The German langue of the order consisted of the priories of Germany, Poland, Dacia (Denmark and Sweden) and Hungary. The history of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg within the German Priory, begins with the establishment of the oldest house of the Order, on the Elbe, in 1160. It had become largely self-dependent, taking over much property from the Templar Order, when that was dissolved in 1312. This greatly increased the assets of the Order in middle and eastern Germany. However, as had already occurred in 1366, the headquarters of the Order had probably sold still more Order estates on their borders to the neighbouring German Order because of the high costs of building defences in Rhodes.

With the 1382 Treaty of Heimbach between the German Grand Prior and the ‘Herrenmeister’, the Bailiwick of Brandenburg attained official autonomous status within the structure of the German Priories. The leaders of the prebends (commanderies) selected the head of the Bailiwick, who was then confirmed in his post by the German Prior. This procedure was confirmed in 1383 by the Chapter General of the Order in Valencia and later also by the Curia and by the Margrave of Brandenburg as head of State. Thus the Bailiwick of Brandenburg acquired special rights enjoyed by no other in the Order.

When the House of Hohenzollern, which had supplied the margraves and Kurfürsten of Brandenburg since 1415, turned to the teachings of Luther in 1538, a few commanders (Komtures) followed suit and later married. This would have made them more dependent on the State rulers. Following protests from the German Grand Prior, in 1551 one provincial Chapter ruled that married commanders should lose neither their honour nor their prebends. Measures to contest this by the Grand Master of Malta remained unsuccessful; and the Bailiwick of Brandenburg was still regarded as belonging to the Order. In the Treaties of Westphalia of 1648, the Kurfürst of Brandenburg was recognised as Protector of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg, a move which was to have far-reaching consequences. After 1693, the office of Herrenmeister was always filled by members of the House of Hohenzollern. In an Order of 1745, King Friedrich II of Prussia commanded that the cross of the Order should be added to the crown of the Prussian king; this is still shown in the Cross of Rechtsritter and Kommendators.

To repay the huge debts arising from the Prussian defeat by Napoleon, King Friedrich Wilhelm III commandeered all clerical estates including those of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg in 1810/11. The German Grand Priory had been dissolved in 1806 and the old Order of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg followed soon after. But as early as May 1812, Friedrich Wilhelm III had founded, in honourable memory of the old Bailiwick, a royal Prussian Order of St John as an honour for services, the decoration for which was the simple cross of the Order in the form of today’s Iron Cross. Members of the former Bailiwick were also admitted to this royal Order. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia then reinstated the Bailiwick of Brandenburg of the Order of the Knights Hospitaller of St John of Jerusalem by a cabinet Decree of October 1852.

Eight knights had formed a Chapter from the old Bailiwick and elected as new Herrenmeister Prince Friedrich Carl Alexander of Prussia. Following the agreements in the Hambacher treaty of 1382, he reported his election to the representative of the Grand Master of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta in Rome, Count Colloredo-Mels, because since 1806 there had been no further German Grand Priors. As Protector, the King commanded that all members of the Royal Order of St John should be admitted as Honorary Knights in the Bailiwick and that they could also be named Rechtsritter.

In the spirit of the times, the Order dedicated itself to caring work. It opened hospitals, created the Institute of the Johanniter Sisters, and was also substantially involved in the founding of the International Red Cross in 1836. During the wars of 1864, 1866, 1870/1, as well as in World War 1, it was successfully involved (often together with the Order of Malta) in the running of military hospitals and in the transport of the wounded. During the Third Reich, the activities of the Order were greatly reduced. As active members of the Resistance, 14 Johanniter members sacrificed their lives.

Making a new start after 1945 was especially difficult because of the division of Germany. Nevertheless the Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe (Johanniter Accident Aid) was set up in 1952; and the Johanniter Sisterhood and the Johanniter Community Aid enterprises followed. All three helped care for the suffering in the difficult conditions of that time. After the reunification of Germany, the Order once again faced great challenges which it has successfully tackled.

Today, the Johanniterorden is divided into 18 German Fellowships/Prebends along regional lines. In addition, it holds formal responsibility for five non-German Fellowships (commanderies) in Finland, Hungary, Austria, France and Switzerland. Outside Europe, the Order is also represented in the USA, Canada, the Baltic States, in parts of Latin America and Namibia. Current membership is around 3,400 Johanniter knights.

The head of the Order is the Herrenmeister. Since September 1999, this post has been filled by Oscar, Prince of Prussia. The Herrenmeister is represented by a Governor (Ordensstatthalter) when he cannot carry out his duties for an extended period. The Captain of the Order is responsible for all legal and honorary matters within the Order. Every Fellowship/Prebend is led by a Commander (Kommendator). The person at the head of the Order and the Kommendators make up the Chapter – the most important decision-making body. Its decisions are carried out by the Government of the Order under the Chancellor of the Order.

HRH Oscar, Prince of Prussia assumed his high office on 5 September 1999, as the sixth Herrenmeister since the re-introduction of the Johanniter Order in 1852. He took over from his father, HRH Wilhelm-Karl of Prussia who had been head of the Order for 41 years.

The English estates of the order were originally subject to the priory of St Gilles in southern France, but in 1185 the priory (later grand priory) of England was established with its headquarters in Clerkenwell. The Order had acquired the site in about 1140 and the modern Order still partly occupies it today. It flourished during the next four centuries; and the Gatehouse of the Priory headquarters was rebuilt in 1504. However, in 1540 the Order was suppressed by King Henry VIII. Despite a brief recovery under Queen Mary, the Order lost all its property although it was never formally dissolved.

In its present form, the Order in England traces its origins to the mediaeval Order through action by French Knights of Malta following 1798. The organ which emerged following that initiative was fostered partly by a movement in England which was inspired by the “age of chivalry”. The question remained how to link this movement with a desire to help the sick and needy, as the Hospitallers of old had done. By the middle of the century, public opinion was appalled by the number of accidents in the workplace, where casualties died or were unnecessarily injured through lack of skilled help. Gradually, this thought crystallised into the support for the teaching and practice of First Aid. First, the St John Ambulance Association was established in 1877 to teach First Aid to the public. Then, 10 years later (1887), followed the creation of the St John Ambulance Brigade, which provided well-trained volunteers to give First Aid cover at public events. These two Foundations are now merged under the title of “St John Ambulance”. Meanwhile, in 1882, thanks to the personal intervention of the Prince of Wales with the Sultan of Turkey, the Order set up a further Foundation: an ophthalmic hospital in Jerusalem – which remains there, doing invaluable work, to this day. All this persuaded Queen Victoria, in 1888, to grant a Royal Charter which affirmed the status of the Order in England. Since then, the reigning monarch, at present HM Queen Elizabeth II, has always been Sovereign Head of the Order, with a junior member of the Royal Family (for the last half century, the present Duke of Gloucester and his father) acting as Grand Prior. The Order is thus a fully recognised Crown Order of Chivalry in Britain.

Meanwhile, the Order, and particularly the work of its Foundations, soon spread throughout the former British Empire. Autonomous “priories” were established in Scotland (1947), Wales (1918), South Africa (1941), New Zealand (1943), Canada (1946), and Australia (1946). The United States of America became the seventh Priory in 1996. More than 30 other branches, called “National Councils” were also set up, mainly in what are now described as “developing Commonwealth countries”. In addition there are Commanderies in Northern Ireland (Ards) and Western Australia; and associated St John bodies in Hong Kong, and the Republic of Ireland.

In October 1999, the Order entered a new phase of its long history. Under the new constitution, which came into force then, the Grand Council became the central governing body of the Order. This now includes 8 Priories, the most recent being a new Priory of England (the original home of the Order). Relations with the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (Roman Catholic, with its Headquarters in Rome) are good; and in the UK, there has in recent years been excellent practical collaboration over providing homes for the elderly.

Brothers of the Order of St John arrived in Sweden around 1170 and founded before 1185 a monastery in Eskilstuna at the grave of the martyr St Eskil, 100km west of Stockholm. The monastery soon became a centre for the cure of the old and infirm. The Swedish Royal Houses and important noble families became generous donors to St John and Eskilstuna. During the 14th century a smaller monastery was founded in Stockholm where goods and other tributes were stored. From Stockholm, they were sent further to the headquarters of the Priory of Dacia. At the end of the Middle Ages, the Order also acquired a church in Stockholm and a monastery in the southeast of the country close to the town of Kalmar. In 1467 leading Swedish members of the Order had direct independent links with Rhodes. The reformation in 1527 ruled by King Gustav I resulted in the temporary extinction of the Order in Sweden.

During the last centuries, Swedish nobles became knights of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg. Among them a Swedish Commandery of the Order was founded in 1920 under the protection of King Gustav V and Queen Victoria; but the Commandery was formally still affiliated to the Bailiwick of Brandenburg until 1946.

In November 1946, Johanniterorden I Sverige was embodied by a Royal Charter with King Gustav V as its Herre och Mästare (Sire and Master). Today HM King Carl XVI Gustav is the High Patron and HM Queen Silvia the First Honorary Member of the Order. Its headquarters have been at the Riddarhuset in Stockholm. The Order has semi-official status, and has about 330 members of whom at least 50 are Knights of Justice. The Order aims to promote Christian values. Knights have to belong to the Swedish Church or another Christian Evangelical Church and acknowledge the Christian faith.

Kommendatorn (the Commander) is in charge of the Order, assisted by Konventet (the Chapter) with a maximum of twelve members. The highest decision-making body of the Order is Riddardagen (the Annual Meeting). Beneath the Chapter, the Order is organised in four regions: Southern, Western, Eastern and the Stockholm area.

Emblem, standard and decorations

The legally protected Emblem of the Order is the white Amalfi cross with sheaves connecting the arms of the cross. The Standard is in red and blue, white and gold, showing the white cross twice iterated on a red background and three open crowns (the coat of arms of Sweden) in gold on a blue background. The knights wear a breast cross and collar cross in white enamel. The collar cross worn on a black silk ribbon with white edged stripes, again has sheaves connecting the arms with the cross. For the knights of Justice, these are crowned by a royal crown in gold (also protected in law).

The full name of the Order is Johanniter Orde in Nederland, Nederlandse tak van de aloude Orde van het Hospitaal van Sint Jan te Jeruzalem (Order of St John in the Netherlands, Dutch branch of the ancient Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem). The Hospitallers were mentioned in the Netherlands for the first time in 1122 in Utrecht as Jerosolimitani. The Bailiwick of Utrecht of the Hospitaller Order of St John had from that time hospitals and Commanderies in all other parts of the Netherlands. The Bailiwick was part of the German Langue. After the Reformation, the Dutch Johanniter Knights came under the Order’s Bailiwick of Brandenburg, after this Bailiwick became protestant (c.1550 – see above).

On the instigation of HRH Prince Hendrik of the Netherlands, consort of HM Queen Wilhelmina, a Dutch Commandery of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg was created called Commenderij Nederland, of which all Dutch Knights became part. It was instituted by Royal Decree of 30 April 1909. The Dutch branch became independent of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg by a Royal Decree of 5 March 1946.

The Order is ruled by the Chapter, headed by the Landcommandeur. H.R.H. the late Prince Bernhard of The Netherlands was till his death Landcommander. H.M. Queen Beatrix is Commander of Honour. Membership of the Order is limited to the Protestant Dutch nobility and is divided into three classes: Honorary Knights and Dames of the Chapter, Knights and Dames of Justice, and Knights and Dames of Grace. HRH the Prince of Orange, Crown Prince of the Netherlands, is Knight of Justice.

The Order continues its ancient charitable and Hospitaller mission supporting several hospitals and hospices. There is a close co-operation with the Dutch branch of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta: there are four joint Commanderies in the Netherlands together with them. A Joint Association for young aspirant Johanniter and Maltese Knights and Dames is also active.

At the beginning of the 1920s, about a dozen knights, Swiss and German, members of the Balley Brandenburg, were living around Bern. In 1937, with the approval of the “Herrenmeister” Oscar Prince of Prussia, they created an “Association of the knights of St John in Switzerland” as a part of the Balley Brandenburg. The “Swiss Society of the Order of St John” was set up in 1948 and became the “Swiss Commandery of the Order of St John” in 1975. Five other sub-commanderies have been created: Geneva (1959), Zurich (1961), Basel (1966), Neuchâtel (1971) and Vaud (1976). In 1962 a Relief Organization (Hilfswerk/Oeuvre d’Entraide) has been created, which since then has been active abroad as well as inside Switzerland. In the year 2000, the Swiss Commandery had about 100 members, as well as some 30 guest knights being mostly German and Hungarian nationals.

The French Commandery of the Order of St John originated with the nomination as Knight of Honour of General Hugues de Cabrol in 1957. A few other Knights were created shortly thereafter and founded the Association of the French Knights of the Order of St John. In the context of the reconciliation between France and Germany, with the help of the Swiss Commandery and the Sponsorship of the Sovereign Order of Malta, the Order was officially recognised by the Grand Chancery of the Legion of Honour by a Decree of 21 April 1960 and the French Commandery was founded and recognised that same year. Created originally with ten Knights, the French Commandery of the Order now counts over sixty members.

The Order is organised in France around two Associations: the Commanderie Française du Grand Baillage de Brandenbourg de l’Ordre des Chevaliers de Saint Jean de l’Hôpital de Jérusalem which groups the French Knights, and the Oeuvres de Saint Jean which develops charitable activity under the leadership of the Commandery and is open to all.

The earliest link between the Order of St John and Hungary dates back to 1135 when Petronilla, a Hungarian noble woman, established a hospice in the Holy Land for the use of pilgrims. Witness to this donation was Raymond du Puy, second grand Master of the Order of St John. In 1147, the second Crusade passed through Hungary and the first hospice of the Order was established by King Geza II of Hungary close to the city of Esztergom. For several centuries, the Order of St John maintained a number of hospices and fortresses scattered across the Kingdom of Hungary in its defence against the infidels. During the Turkish occupation of a large part of Hungary and the ever strengthening Habsburg rule, the Order lost progressively all its possessions and influence in Hungary.

By the beginning of the 20th century, 32 Hungarian protestant noblemen were members of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg (Johanniter Orden). In 1924, with permission from the Herrenmeister HRH Eitel-Friedrich of Prussia, the Hungarian knights established their own national and autonomous Commandery, the Johannitarend Magyar Tagozata. The Sovereign Military Order (catholic) set up direct diplomatic relations with the Kingdom of Hungary in 1925, before establishing a national association in 1928. Both organisations maintained significant hospices and charities before and during the war. After WWII, these associations continued their work in exile providing help to refugees. The Hungarian Johanniter Commandery was welcomed back officially to Hungary in 1990, where it maintains co-ordinated and fraternal relationships with its catholic brethren.

The roots of the Finnish Commandery of the Order of St John can be traced back to the Bailiwick of Brandenburg: in the 14th century this was granted an almost autonomous position within the Order which it retained until 1811. As noted on p.3 above, the Napoleonic wars placed a heavy burden on the northern parts of Germany; all the Bailiwick’s possessions were confiscated by the Prussian State in 1811. The Knights, however, were given as thanks and in memory of the Bailiwick, an Order of Merit granted by the newly created Royal Prussian Order of St John (founded for this purpose). But new winds started to blow. In 1852, the former Bailiwick of Brandenburg was re-instituted by King Fredrik Wilhelm IV, who summoned its surviving Knights to a meeting, where it was decided to resume the mediaeval Bailiwick’s activities. Large donations flowed from this decision, making it possible to resume charitable work on a significant scale.

The contemporary Finish branch of the Order of St John

A number of knights from the early 19th century, seem likely to have originated from the “Russian episode” in the history of the Sovereign Order of St John of Malta: i.e. knighthoods conferred by Tsar Paul I, who had declared himself Grand Master 1799-1801 (the Pope never confirmed him as Grand Master). Later, others were derived from the interim period of the Bailiwick (i.e. the Royal Prussian Order of St John, mentioned above). The first knight of the reborn Bailiwick of Brandenburg living in Finland, was Baron Anders Ramsay, born in 1799, who was made a Knight of Justice by the Herrenmeister in 1870. In 1923, the Finnish knights, by then a total of 15, organised themselves into a subchapter. This received the consent of the Chapter General of the Bailiwick of Brandenburg in 1925, and was reflected in statutes in 1935. By 1933 the subchapter had 19 members, but after the Second World War the number fell to 14. Since then, recruitment has been cautious but steady.

In 1949 permission was given for establishment of a separate Finnish Commandery. The members of the Commandery met together for the first time on 18 May 1950, by which time there were 47 knights. The first commander was Baron Ernst Fabian Wrede. He was succeeded in 1952 by Woldemar Fredrik Hackman (1952-1961), followed by Count Carl-Johan Georg Creutz (1961-1987), Professor Nils Christian Edgar Oker-Blom (1987-1995), and (since 1995) Magnus Gabriel von Bonsdorff.

Although the German Johanniter Order has opened its ranks to non-nobles, the Finnish Commandery remains limited to the Finnish nobility, proof of which is regulated by the Finnish House of Nobility. The Order has official recognition in Finland and its decorations can be worn on all occasions, including with military uniforms.

There are now 173 members, including two commanders (one serving, one formerly serving), one honorary commander, 16 knights of Justice and 154 knights of Honour. The Commandery is governed by a Chapter of nine members, consisting of the Commander, Judge (responsible for regulating statutes and membership), Director (Verkmästare responsible for the activities of the Commandery), Treasurer (responsible for the accounts), and the Secretary General (responsible for correspondence and keeping the minutes of meetings), and four Councillors. The Chaplain, Master of Ceremonies and Nurse (who is not a member of the Order) are not members of the Chapter.

The first statutes for the separate Finnish Commandery were drawn up and approved on 18 May 1950, before being confirmed by the Herrenmeister and enacted under Finnish law on 5 May 1951. They were amended on 6 February 1996, to allow for the Commander to be elected for a six-year term with the option of being re-elected for three years at a time. Members of the Chapter are elected for a three-year term with the options of being re-elected

| Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Breast star of Knight of Grace of the Order of St John |

|

| Awarded by Sovereign of the order | |

| Type | Order of chivalry |

| Motto | Pro Fide Pro Utilitate Hominum[1] |

| Day | 24 June[2] (Feast of John the Baptist) |

| Status | Currently constituted |

| First Sovereign | Victoria |

| Sovereign | Elizabeth II |

| Grand Prior | Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester |

| Grades (w/ post-nominals) | Bailiff/Dame Grand Cross (GCStJ) Knight/Dame of Justice or Knight/Dame of Grace (KStJ/DStJ) Commander/Chaplain (CStJ/ChStJ) Officer (OStJ) Serving Brother/Sister (SBStJ/SSStJ) Esquire (EsqStJ) |

| Precedence | |

| Next (higher) | Dependent on State |

| Next (lower) | Dependent on State |

| Ribbon of the order | |

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia: (Redirected from Venerable Order of Saint John)

The Order of St John,[3] formally the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (French: l’ordre très vénérable de l’Hôpital de Saint-Jean de Jérusalem[n 1]) and also known as St John International,[4] is a royal order of chivalry first constituted as such by royal charter from Queen Victoria in 1888. It evolved from a faction of the Order of Malta that emerged in France in the 1820s and moved to Britain in the early 1830s, where, after operating under a succession of grand priors and different names, it became associated with the founding in 1882 of the St John Ophthalmic Hospital near the old city of Jerusalem and the St John Ambulance Brigade in 1887.

The order is found throughout the Commonwealth of Nations,[5] Hong Kong, the Republic of Ireland, and the United States of America,[6] with the world-wide mission “to prevent and relieve sickness and injury, and to act to enhance the health and well-being of people anywhere in the world.”[6] The order’s approximately 25,000 members, known as confrères,[5] are mostly of the Protestant faith, though those of other Christian denominations or other religions are accepted into the order. Except via appointment to certain government or ecclesiastical offices in some realms, membership is by invitation only and individuals may not petition for admission.

The Order of St John is perhaps best known through its service organisations, including St John Ambulance and St John Eye Hospital Group, the memberships and work of which are not constricted by denomination or religion. It is a constituent member of the Alliance of the Orders of St John of Jerusalem.